Freedom Riders are welcomed home to Wold-Chamberlain Field in the Twin Cities. From left in foreground: Marv Davidov, Zev Aelony, David Morton, Eugene Uphoff (with guitar), Claire O'Connor and Robert Baum. (Pioneer Press, File)

FREEDOM RIDERS

The Freedom Riders’ personal stories of awakening and commitment were as complex and diverse as the society which they wanted to transform.

Five of the “Minnesota Six,” as they came to be known, were current or former students at the University of Minnesota. Several were long-term friends who had been part of a bohemian subculture that existed on the fringes of Dinkytown, the sprawling student ghetto in Minneapolis.

All were arrested on June 11, 1961, and convicted and incarcerated in Mississippi’s notorious Parchman State Prison.

Marv Davidov was the oldest of the group. In 1961, he was living in a house owned by Melvin McCosh at the edge of Dinkytown. An art dealer, he was politically and culturally sophisticated and the most radical member of the Minnesota group.

To him, becoming a Freedom Rider was a natural and connecting link to an activist career that led to regional, and even national, notoriety in the 1970s and 1980s. A tireless proponent of nonviolent civil disobedience, he eventually helped to organize movements against the draft, nuclear power plants, high voltage power lines, and the Honeywell Corporation’s production of military technology.

David Morton, a Unitarian and self-styled “mountain man,” who spent part of 1961 in Jackson Hole, Wyoming, was a talented musician who expressed his dissatisfaction with the mainstream through folk ballads and protest songs.

An occasional sideman for a rising Minnesota folk singer named Bobby Zimmerman, Morton added a lyrical and quixotic touch to the growing community of Freedom Riders. He lived on the fringes of Dinkytown where he taught guitar lessons to a young Ossian Or, who recalls having a lesson cut short when Dave had to catch the Freedom Ride bus that had stopped outside his apartment to pick him up.

Zev Aelony was a political science major at the University of Minnesota. His dual commitment to CORE and racial justice prepared him for the later civil rights struggles and Freedom Rides in Florida, Georgia, and Alabama.

Bob Baum was a nineteen-year-old college dropout whose attraction to existential philosophy led him to a deep and abiding distrust of social and political complacency.

Gene Uphoff was a nineteen-year-old medical student and Quaker, who also performed as a folk and rock guitarist in several local coffee houses in Dinkytown. After the Freedom Rides, he attended the University of Colorado Medical School and later opened a series of government-sponsored “storefront” clinics for the poor.

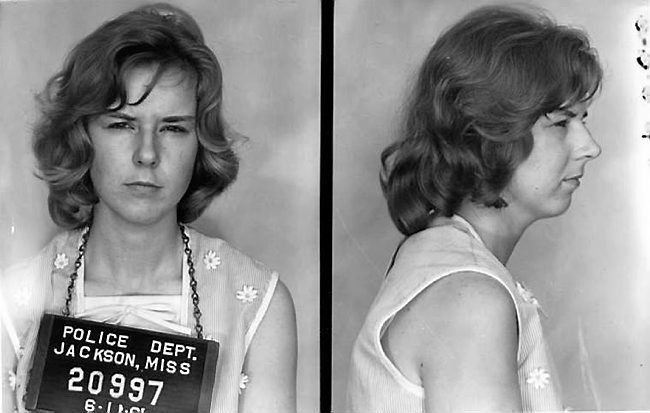

Claire O'Connor

Claire O’Connor, a twenty-two-year old Boston-born Catholic who worked as a practical nurse at the University of Minnesota Hospital, was the daughter of a politically active mother and deceased father who had worked as a union organizer.

One of the seven Freedom Riders from Minnesota, she was one of the young civil rights advocates who put their convictions and their fannies on the line by integrating and riding buses across state lines through the segregated South during the turbulent summer of 1961. OConnor was the only woman among the small contingent of mostly University of Minnesota students who challenged segregation laws at bus depots, airports and train stations after Southern states thumbed their noses at U.S. Supreme Court rulings declaring such public transportation segregation practices unconstitutional.

Vietnam Protests

The protest that developed in conjunction with the Vietnam War was "the largest and most effective antiwar movement in American history," according to Melvin Small in The Oxford Companion to American Military History.

In Minneapolis, one of the first organized protests was a Peace March that was planned for August 5, 1967 to commemorate the bombing of Hiroshima and to protest the U.S.'s increasing involvement in Viet Nam.

The march was to start at the Mayo Auditorium on the St. Paul Campus of the University of Minnesota and travel down Raymond and University Avenues to end in Dinkytown.

About 5,000 demonstrators rallied on May 5, 1970 to protest President Nixon's expansion of the war into Cambodia, part of a national wave of protests that included the shooting of four demonstrators at Kent State University in Ohio. Kent State was the incubator for student strikes.

At the University of Minnesota, instructors and teaching assistants cancelled classes and groups met either on campus, in Dinkytown, or in people’s homes to plan for door knocking to explain the anti-war position and initiate a grass roots effort to change the government.

University antiwar efforts stepped up in the spring of 1972. The "Eight Days in May," as the period of unrest from May 9-16, 1972 came to be called, witnessed the largest, most violent University demonstrations of the Vietnam War era.

On April 16, a crowd of protesters marched through the campus and Dinkytown, following a published schedule of antiwar activities. The plan included a noon rally at Morrill Hall, followed by an occupation of the Air Force recruiting office in Dinkytown and the ROTC office on campus. About 1,500 demonstrators attended the rally; 800 moved toward Dinkytown afterward.

On May 8, 1972, it was announced that the U.S. was blockading and mining Haiphong Harbor. The next day 1,500 students held a rally on Northrop Mall. On May 10, 3,000 students broke into the Army recruiting station and marched to the Armory.

"At about 1 p.m. on May 10, 1972, Eugene Eidenberg was standing on the lawn of the Armory building, watching paper fall from broken windows. It was windy that day; the papers blew unpredictably, just as some of the rocks the protesters were throwing missed their targets.

"Near the Armory, along University Avenue, the demonstrators were tearing down an iron fence. An overturned 1962 Chevrolet was on fire near 18th Avenue. A small contingent of University police, dwarfed in numbers by the 3,000 protesters, was guarding the locked Armory doors.

❦ READ MORE: May 1972: antiwar protests become part of U history

The students then marched to Coffman Union, where they put up barricades and occupied Washington Avenue. Minneapolis police gathered at Koehler's Garage in Dinkytown, now the site of the Purple Onion, waiting for a call to action. University Vice President of Administration Eugene Eidenberg contacted Mayor Charles Stenvig, who ordered the police on campus.

The police marched down Washington Avenue toward Oak Street, proceeding to beat up students on bridges, spreading teargas up and down the mall, and clubbing protesters. Oak Street demonstrators were pushed toward Northrop Mall. Some joined the Church Street group. About 500 congregated in Dinkytown.

In a final effort to break up the crowds, a police helicopter flying over Dinkytown sprayed tear gas on the assembled protesters. Dinkytown residents closed their windows to keep the wind from blowing tear gas into their homes.

Thirty-three protesters were arrested on May 10. Twenty protesters and seven policemen were hospitalized with injuries.

After the gas cleared, demonstrators began tearing fences and gathering debris to build a barricade blocking Washington Avenue at Church Street. Governor Wendell Anderson called in the National Guard. The Guard arrived on campus at 1 a.m. on May 11. Shortly after 5 a.m. on May 12, two units of Minneapolis police cleared the barricade, dispersing 150 people.

The May demonstrations were the last major antiwar protests at the University, and part of the last wave of protests nationally. U.S. military involvement in Vietnam ended in January 1973. After years of disturbances, the University and other college campuses were quiet.

DRAFT RESISTANCE AND THE MINNESOTA 8

Seven of the Minnesota 8 then and now: Front row (from left) are Chuck Turchick, Mike Therriault (with book), Brad Beneke (head turned) and Don Olson. Back row (from left): Pete Simmons, Bill Tilton and Frank Kroncke. Missing: Cliff Ulen

Courtesy of Cheryl Walsh Bellville

The early meetings of the Vietnam mobilization against the war began in 1966 in Dinkytown, in the basement of the Wesley Foundation at 12th Avenue and 4th Street S.E.

According to Don Olson, the people who met there were very much involved with the draft resistance movement, planning the Draft Information Center and scheduling speakers at Dinkytown churches and other locales.

On July 10, 1970, eight men were arrested while trying to break into government offices in three Minnesota towns — Little Falls, Alexandria and Winona — to destroy draft records. During subsequent trials, they were dubbed "The Minnesota 8," and their defenses centered on their opposition to the Vietnam War and the use of the draft to force men to fight it.

The eight were initially charged with attempted sabotage of the national defense, an offense carrying a hefty prison sentence. But the charge was later reduced to attempted burglary.

The defendants, whose ages ranged from 19 to 26, were Bill Tilton, Frank Kronke, Cliff Ulen, Chuck Turchick, Mike Therriault, Brad Beneke, Don Olson—born and raised in Dinkytown—and Pete Simmons. Protesters marched in front of Bridgeman’s in Dinkytown in support of them.

Molly Ivins, a nationally known columnist, then a reporter for the Minneapolis Tribune wrote a profile of the eight defendants:

"One is a theology teacher, another a conservation commissioner in Brooklyn Center, another a member of Phi Beta Kappa; another was vice president of the student body at the University of Minnesota; another was a fraternity president, and three had planned to be lawyers." Ivins went on to label the defendants "The Sons of the Establishment."

Ulen pleaded guilty to burglary and was given probation. “The Minnesota 8” became the “Minnesota 7.”

Each of the remaining seven was tried, convicted and sentenced to five years in prison, though none served more than 20 months. A number never strayed far from idealistic causes. Don Olson, for example, got involved in the food co-op movement and became a local liberal pundit; he currently hosts a local talk-radio show on KFAI.

❦ READ MORE: 'Peace Crimes' tells Minnesota 8's war story

RED BARN PROTEST

On April 30, 1970 the Nixon Administration announced the invasion of Cambodia.

On Monday, May 4, 1970, 5,000 students and faculty members voted to strike the University in opposition to the United State offensive in Cambodia and the possible resumption of bombing in Cambodia.

The strike—supported by across-section of students and faculty members—encompassed radicals,moderates, and liberals. On Saturday, May 9, a large crowd of students, faculty members, citizens, veterans, and clergymen marched from the University to state capital. Student groups from Augsberg, Macalester, St. Thomas, Hamline, St. Catherine’s, and Concordia joined the throng as the march passed their campuses.

Estimates of the size of the crowd varied from 20,000 to 50,000.

○

A separate protest occurred just north of the campus, in Dinkytown. On April 1, a group of students had occupied a site where the Red Barn chain had planned to build a fast food restaurant.

About 50 Minneapolis police officers, and an equal number of Hennepin County Sheriff’s deputies armed with rifles andshotguns, took up their positions as helicopters circled overhead. After a brief scuffle, the demonstrators were cleared away and the bulldozers moved in to demolish the four storefront buildings the protesters had occupied.

By six o’clock the next morning, they were a pile of rubble.

The protesters had the last word: a pacific one. By mid-afternoon, the site had been converted into a “People’s Park” by a group of 75 young people, who planted daisies, chrysanthemums, and bachelor’s buttons, all to the sound of rock music.

Red Barn eventually abandoned its plans to open a Dinkytown location.